picture: Paul Munzinger

Dive4Diadema – Citizen Science Underwater

In spring 2023, a mass mortality event of Diadema setosum began in the Mediterranean Sea and spread within a short period of time to the Red Sea. In many areas, this led to the near-complete disappearance of the species. More recently, individual long-spined sea urchins have been observed again, and we hope that they will re-establish themselves along the entire coastline. With your help, we aim to investigate the disappearance and subsequent recolonisation of Diadema setosum and to document the remaining populations.

Join us and be part of the citizen science project Dive4Diadema!

picture: Heinz Krimmer

picture: Paul Munzinger

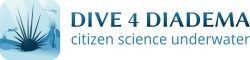

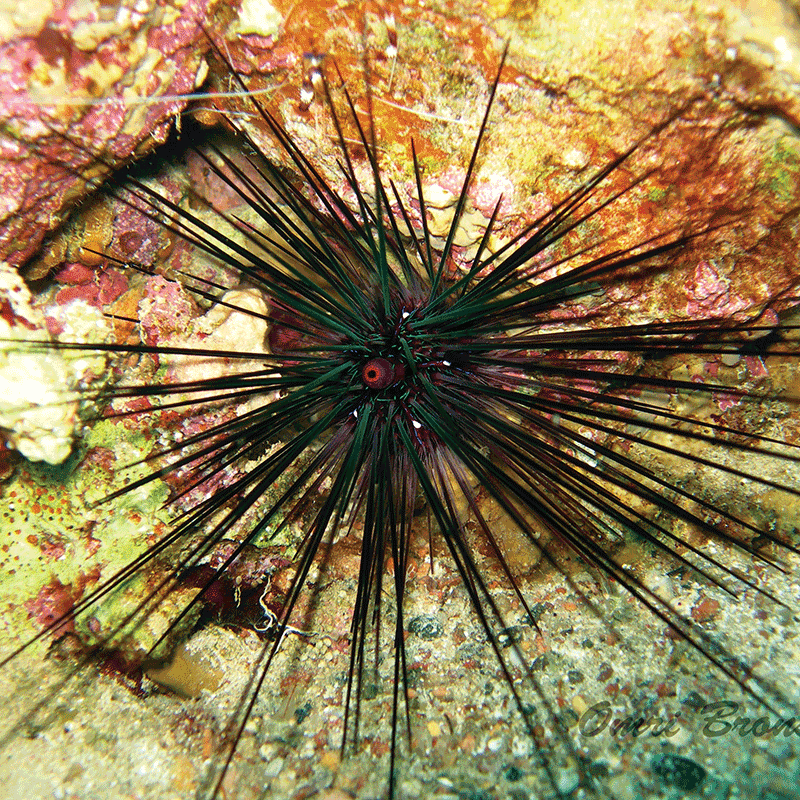

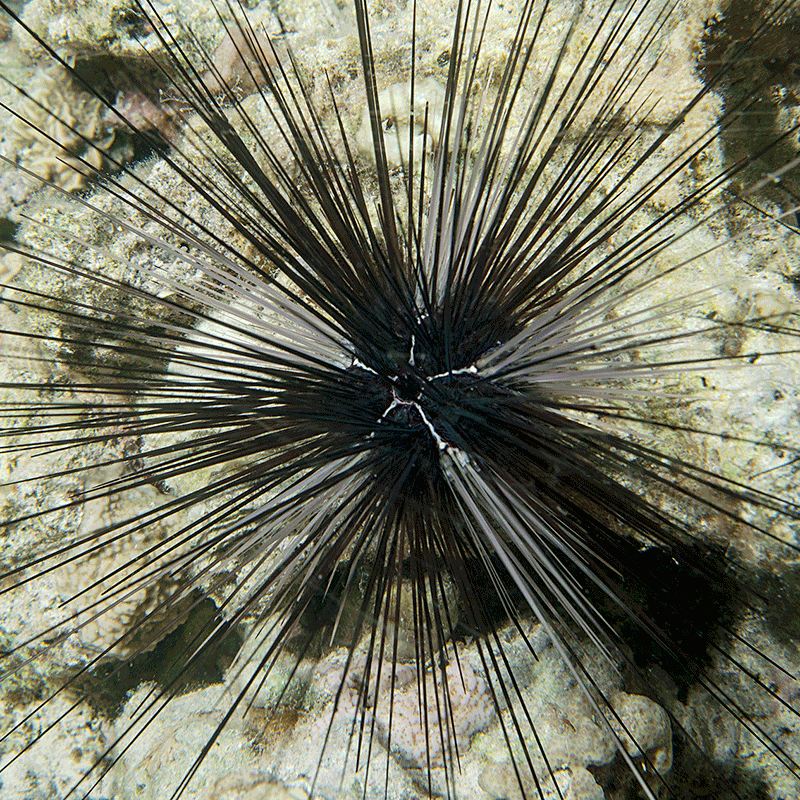

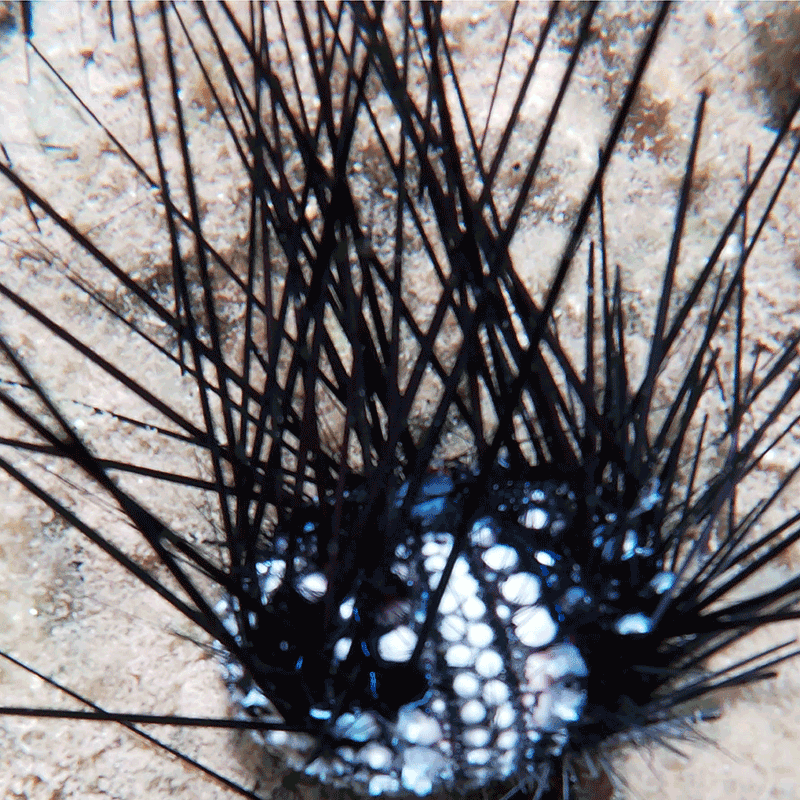

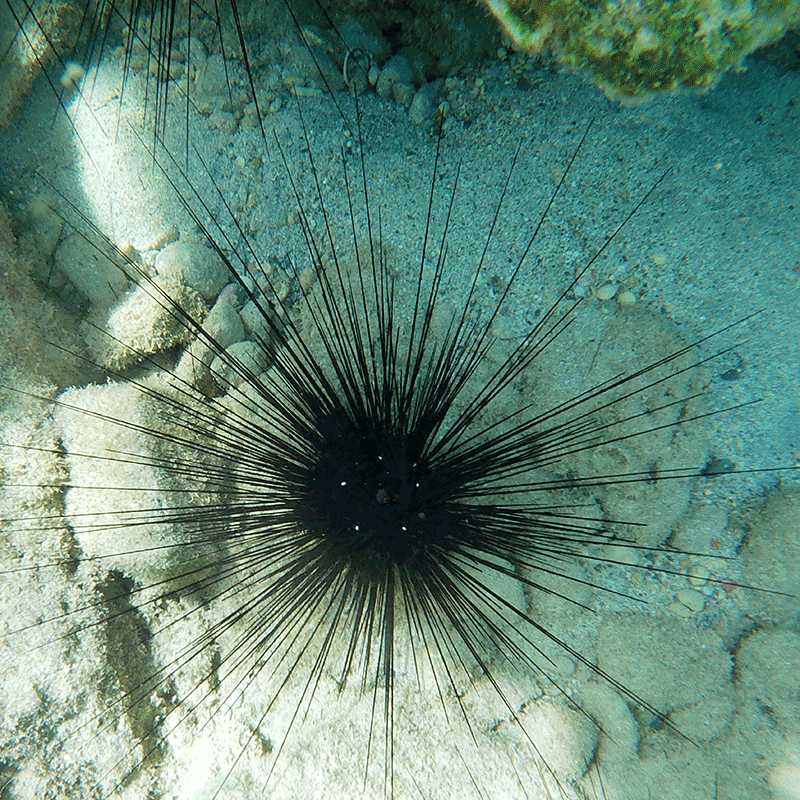

What do they look like?

Diadema setosum (Leske, 1778) has extremely long, black, hollow spines. It can be distinguished from other species by five characteristic white dots on its body. Another distinguishing feature of the species is the presence of a bright orange ring around the anal cone on the upper side of the body. However, some individuals lack the white dots or the orange anal ring (or both), although the majority have them.

Where do they live?

They are native to the Red Sea, on the African east coast and in the western Indo-Pacific. As a member of the neobiota, Diadema setosum invaded from the Red Sea into the Mediterranean basin through the Suez Canal in 2006, and, currently, is among the established non-indigenous species of the basin. However, two groups can be genetically distinguished. One group was originally restricted to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf and has recently migrated to the Mediterranean. The other group is found on the east coast of Africa and in the western Indo-Pacific.

picture: Oliver Meckes

picture: Oliver Meckes

Why they are so important?

Diadema setosum is a crepuscular and nocturnal species that was once ubiquitous. As grazers, they restrict algal growth, clearing up space for larval settlement of other species and restraining algal proliferation that may outcompete slower growing organisms, such as corals.

Sea urchins in danger!

In spring 2023, a mass mortality event of Diadema setosum began in the Mediterranean Sea and rapidly spread to the Red Sea. In many areas of the Red Sea, this led to the near-complete disappearance of the species. More recently, individual long-spined sea urchins have been observed again, and we hope that they will re-establish themselves along the entire coastline. To learn more about this process, your observations are particularly important.

picture: Bardanis Emmanouil

How to join?

All recreational divers are encouraged to report their observations seen during their dives. There is a free, multilingual app for iPhone, iPad und Android smartphones & tablets. Every observation of live and dead diadem sea urchins helps us to learn more about the current mass mortality. Even if no sea urchins are seen on the dive, this is important information to report. Dive4Diadema is a joint effort of recreational divers, dive centres, tour operators training organizations and scientific institutions. Only together can we manage to find and save the last occurrences of the black, long-spined diadem sea urchin.

Join Dive4Diadema!

Follow the button to download the App in the App Store and at Google Play or scan the QR code.

Diadem sea urchins – The Story

picture: Bardanis Emmanouil

Healthy diadem sea urchin in the reef.

“Lawnmowers” of the reefs

Sea urchins are one of the most important animal groups in the coral reefs of the Red Sea. They feed on algae and are therefore the “lawnmowers” of the reefs. They contain the spread of algae and thus create space for the settlement of beneficial larvae and slower-growing organisms, such as corals, mussels and bryozoans. Sea urchins graze on algae removing them from solid surfaces. This feeding activity leads to a strong bioerosion of the substrate that aids the development of other organisms. Particularly industrious are diadem sea urchins. As a group, diadem sea urchins consist of nine species found worldwide in warmer seas. In the Caribbean the diadem sea urchin Diadema antillarum scrapes up to 9.7 kg of calcareous sediment per square meter of coral reef every year. This creates new underwater habitats and white sandy beaches.

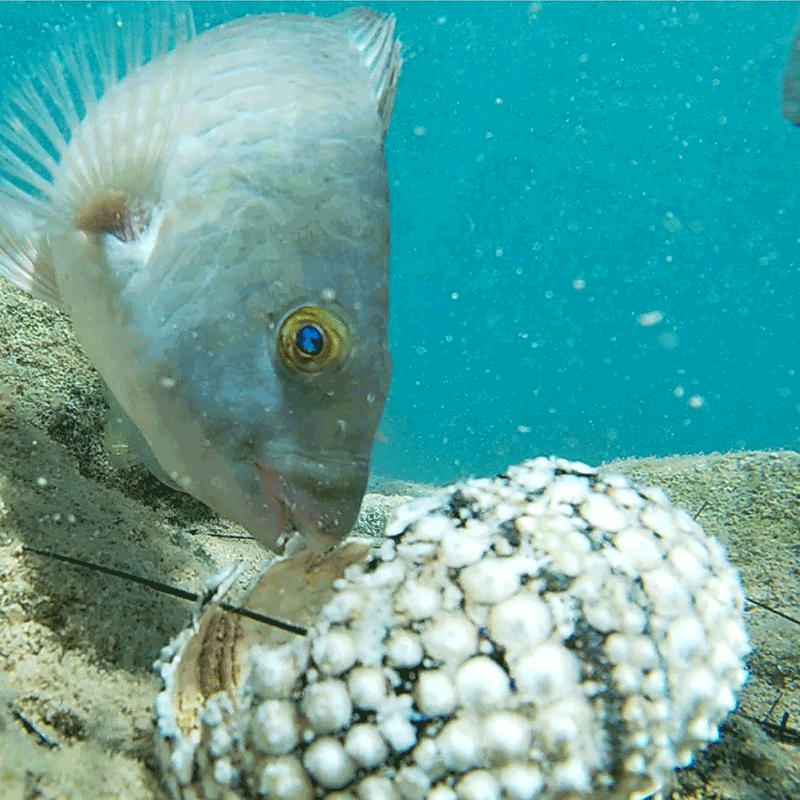

Mass mortality events

Repeated mass mortality events in the Caribbean species Diadema antillarum peaked in the early 1980s due to a waterborne pathogen. In the Caribbean, 98 % of all diadem sea urchins disappeared at that time. The survivors have slowly recovered in recent years, but by 2022, the population crashed again when about 95 % of all sea urchins died. Scientists were able to identify the protozoan Philaster apodigitiformis as the pathogen in the Caribbean, which is also a known parasite in fish. In other regions, however, the bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus seems to be the culprit, which together with high water temperatures led to the mass mortality events. Both pathogens lead to cell death. The first noticeable sign of infection is typically the loss of spines in the diadem sea urchin. In samples from the Red Sea collected during the mass mortality event in January 2023, a unicellular organism similar to Philaster apodigitiformis was detected, indicating an infection with this protist.

picture: Bardanis Emmanouil

Mass mortality events in species of Diadema.

Dramatic changes in the coral reefs

The disappearance led to dramatic changes in the coral reefs and significant reduction of the entire underwater biodiversity in the respective regions. Within a short time, the colourful and species-rich coral reefs were transformed into a reef landscape overgrown with algae and poor in species. In 2009, another mass mortality event took place on the East African coast, in which 65% of the diadem sea urchin species Diadema africanum died, and in 2018, 93% of all diadem sea urchins died around the Canary Islands. These die-offs have led to major changes underwater, with algae spreading vigorously.

Migrated into the Mediterranean

As a native species, Diadema setosum is found in the western Pacific and along the east coast of Africa. Native populations originally restricted to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, have in recent years migrated into the Mediterranean as a neobiot via the Suez Canal, like many other marine animals and plants. In 2006, Diadema setosum was observed for the first time off the coast of Kaş in Turkey. It has expanded along the coasts of Greece, Lebanon, Israel, Libya and the Egyptian Mediterranean coast and is now at home throughout the Mediterranean.

Almost completely disappeared

Dead and dying long-spined sea urchins were first observed in July 2022 off the harbour of Kastellorizo, Greece. What initially appeared to be isolated cases developed into a mass mortality event which, much like the original migration of Diadema setosum from the Red Sea into the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal, rapidly spread in the opposite direction into the Red Sea. Prior to the mass mortality event, densities of up to 30 individuals per square metre of this crepuscular and nocturnal species could be found. Following the outbreak, the species almost completely disappeared along the coast from Aqaba and Eilat to the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula, including the Saudi Arabian coastline, and further south into the Red Sea. Only in recent months have increasing numbers of new sightings of Diadema setosum been reported.

Scientific literature

Omri Bronstein, Andreas Kroh, Yossi Loya (2016). Reproduction of the long-spined sea urchin Diadema setosum in the Gulf of Aqaba – implications for the use of gonad-indexes. Scientific Reports 6:29569.

Menekse Didem Demircan, Elif Özlem Arslan-Aydogdu, Cem Dalyan, Vahap Eldem, Onur Gönülal, İnci Tüney (2025). Mortality event of the Mediterranean Invasive Sea Urchin Diadema setosum from Gökova Bay (Southern Aegean Sea). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, Volume 319,109290.

Peter J. Edmunds, Robert C. Carpenter (2001). Recovery of Diadema antillarum reduces macroalgal coverand increases abundance of juvenile corals on a Caribbean reef. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.98, 5067–5071.

Hans Fricke (1974). Möglicher Einfluß von Feinden auf das Verhalten von Diadema-Seeigel. Marine Biology 27: 59-62.

John Edward Gray (1825). An attempt to divide the Echinida, or Sea Eggs, into natural families. Annals of Philosophy, new series. 10:423-431.

Ian Hewson, Isabella T. Ritchie, James S. Evans, Ashley Altera, Donald Behringer, Erin Bowman, Marilyn Brandt, Kayla A. Budd, Ruleo A. Camacho, Tomas O. Cornwell,Peter D. Countway, Aldo Croquer, Gabriel A. Delgado, Christopher De Rito,Elizabeth Duermit-Moreau, Ruth Francis-Floyd, Samuel Gittens Jr, Leslie Henderson, Alwin Hylkema, Christina A. Kellogg, Yasunari Kiryu, Kimani A. Kitson-Walters, Patricia Kramer, Judith C. Lang, Harilaos Lessios, Lauren Liddy, David Marancik, Stephen Nimrod, Joshua T. Patterson, Marit Pistor, Isabel C. Romero, Rita Sellares-Blasco, Moriah L. B. Sevier, William C. Sharp, Matthew Souza, Andreina Valdez-Trinidad, Marijn van der Laan, Brayan Vilanova-Cuevas, Maria Villalpando, Sarah D. Von Hoene, Matthew Warham, Tom Wijers, Stacey M. Williams, Thierry M. Work, Roy P. Yanong, Someira Zambrano, Alizee Zimmermann, Mya Breitbart (2023). A scuticociliate causes mass mortality of Diadema antillarumin the Caribbean Sea. Sci. Adv.9:eadg3200.

Alwin Hylkema, Adolphe O. Debrot, Esther E. van de Pas, Ronald Osinga, Albertinka J. Murk (2022). Assisted Natural Recovery: A Novel Approach to Enhance Diadema antillarum Recruitment. Front. Mar. Sci., Sec. Coral Reef Research, Volume 9: 929355.

Nathanael Gottfried Leske (1778). Jacobi Theodori Klein naturalis dispositio echinodermatum . . ., edita et descriptionibus novisque inventis et synonomis auctorem aucta. Addimenta ad I. T. Klein naturalem dispositionem Echinodermatum. G. E. Beer, Leipzig,

H. A. Lessios, D. R. Robertson, J. D. Cubit (1984). Spread of Diadema mass mortality through the Caribbean. Science 226, 335–337.

Ola Mohamed Nour, Sara A.A. Al Mabruk, Mohammed Adel, Maria Corsini-Foka, Bruno Zava, Alan Deidun, Paola Gianguzza (2022). First occurrence of the needle-spined urchin Diadema setosum (Leske, 1778) (Echinodermata, Diadematidae) in the southern Mediterranean Sea. Bioinvasions Rec.11, 199–205.

Fikret Öndes, Vahit Alan, Michel J. Kaiser, Harun Güçlüsoy (2022). Spatial distribution and density of the invasive sea urchin Diadema setosum in Turkey (eastern Mediterranean). Marine Ecology 43:e12724.

Quod JP, Séré M, Hewson I, Roth L, Bronstein O. (2024). Spread of a sea urchin disease to the Indian Ocean causes widespread mortalities-Evidence from Réunion Island. Ecology. 2025 Jan;106(1):e4476.

Skouradakis, G., Vernadou, E., Koulouri, P., & Dailianis, T. (2024). Mass mortality of the invasive echinoid Diadema setosum (Leske, 1778) in Crete, East Mediterranean Sea. Mediterranean Marine Science, 25(2), 480–483.

Lachan Roth, Gal Eviatar, Lisa-Maria Schmidt, Mai Bonomo, Tamar Feldstein-Farkash, Patrick Schubert, Maren Ziegler, Ali Al-Sawalmih, Ibrahim Souleiman Abdallah, Jean-Pascal Quod, Omri Bronstein (2024). Mass mortality of diadematoid sea urchins in the Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean. Current Biology, Volume 34, Issue 12, 2693 – 2701.e4.

Rotem Zirler, Lisa-Maria Schmidt, Lachan Roth, Maria Corsini-Foka, Konstantinos Kalaentzis, Gerasimos Kondylatos, Dimitris Mavrouleas, Emmanouil Bardanis, Omri Bronstein (2023). Mass mortality of the invasive alien echinoid Diadema setosum (Echinoidea: Diadematidae) in the Mediterranean Sea. R. Soc. Open Sci.10:230251.

Supporters

The Citizen Science Project Dive4Diadema is supported by the following dive centres, dive shops, tour operators, training organisations and scientific institutions.

Newsletter

What content can I expect? Dive4Diadema will be happy to inform you about the projects if you subscribe to our newsletter with an email address.

Double-Opt-In and Opt-Out

You will receive a so-called double-opt-in e-mail in which you will be asked to confirm your subscription. You can object to receiving the newsletter at any time (so-called opt-out). You will find an unsubscribe link in every newsletter or double opt-in e-mail.

Dispatch of the newsletter

The newsletter is sent via the WordPress Plugin “Newsletter”, which also stores the e-mail addresses and further information about the dispatch of the newsletter.

Data protection information

Detailed information on the dispatch procedure and your revocation options can be found in our data protection declaration.

Support the citizen science project Dive4Diadem with a donation!

How can I donate?

Send a donation conveniently via the Paypal button or bank transfer to:

aquatil gGmbH, Kreissparkasse Tübingen, IBAN DE84641500200004367220, BIC SOLADES1TUB

What fees do I have to pay?

The PayPal processing fee for donations is 1.5% + €0.35. Normally there are no transfer fees if the money is transferred from bank account to bank account within the SEPA area or EEA (European Economic Area) and in euros.

Questions?

If you have any further questions or need assistance, please, get in touch at info@dive4diadema.org. We look forward to you joining us. Yours Dive4Diadema-Team!

CONTACT US